Bowmen of Winston

Founded November 2014 by John (Master) and Eiann ('Bastard' --including 'Turdy'-- 'Cogsworth', and others following such words as 'great steaming', 'fat', 'slimy', and 'piece of'.)

-------------------------------------------------------------

Skye's the Limit

and

now (October 2019) a link to: New Limits

------------------------------------------------------------------

Early August 2016

The Cuillin Perverse: a bastard's tale

(An adventure planned to span 23rd August to 29th August 2016)

IT'S DRAFTY TODAY (8th Sept 2016)

BUT TODAY IT IS NOT (13th Sept 2016)

Until this time, a dream,

A distant past,

A memory of dreams

A world away;

A hope... made real

At last.

by Turdy Bastard

Thursday, August 18, 2016

'C'mon Cogsworth.' said Master. 'We're going for a walk.'

And so it always begins.

Master had a glint in his eye, if not from sunshine, then mischief; it was not sunshine. I had an impending sense of doom: something big was looming. Suddenly, the shadow of a very large bird bore down upon us as we stepped from Master's thrash-hold onto our narrow little setting-off road. I was very nearly squashed by it. Master dragged me clear by my collar. He has saved many lives; all of them more deserving than my own. Once, he saved an old lady from being run over by a bus.

'Now then,' said master, dusting me off. ' look up there.' he said.

I looked up, fearful lest the bird return.

'What do you see?' he asked.

'Nothing.' I said.

'Look harder. Look again.'

'Another bird?' I said.

'Beyond the bird.' Master said, patiently.

'Tree. Leaves?' I offered, nervous now that Master had begun sharpening a stick.

'And beyond that...?' Absent-mindedly, Master's hand made random short jabbing movements with the stick. Such things I am wont to notice.

'S...Sky?'

'Yes. Yes!' exclaimed Master, 'and what else?'

Unable to see anything else, I remained silent. I could hear the tap-tap of the stick on the side of Master's boot. He seemed a little dismayed that my tiny eyes could not see as far as his.

'Adventure, Cogsworth! The bright glint of adventure! It is like gold, Cogsworth, gold.'

In a poorly disguised pique, he discarded his sharp toy , and added. 'Yes, there is also sky; I see that too. Be not dismayed by your absence of imagination, Cogsworthless. It is not necessarily the tallest among us who have the greater vision, you see. Ah, but then you do not, do you? Indeed, Cogsworth, you are blind. But, as it happens you were very nearly accidentally correct, Skye is exactly where we are going.'

I am slightly wary of heights; little stammering voices inside my head remind me that such things are anathema to me... and sky is, to my way of thinking, a very long way away...upwards. My silence must have seemed to Master as capitulation for it had galvanised him to action. When I finally raised my frightened eyes to meet his gaze, I saw that he had strode some hundred or so paces away; fingers clicking urgently at his back.

'Coming, Master!'

The day had begun its cyclic yielding of its share in the sky space continuum so that the shift of night could begin. Upon our return from a lengthy walk, Master once again clicked his fingers behind him, actually more than once. He pushed open the oaken door to his palace, and I, being conditioned to follow, found myself in a sudden and uncomfortable position. It was beyond my understanding that things could dare to stick to Master's fingers. Natural, then, that he might want to rid himself of that nuisance by flicking them. My own instinct to react without delay to the beckonings of Master landed me in a spot of bother. A 'click' is a click, is it not? For me, it turned out to be another painful lesson in the servitude of greatness. Having one's ear trapped 'twixt slammed door and stoic jamb from evensong to reveille can be a real pain. Is not all pain real? And what is reality? Master says that reality is merely a place in your head. 'A place? ...mmmnnn.' I pondered this wisdom for nearly a whole minute... and then fell asleep.

The next morning, freed from doorly trapitude, I heard with my good ear, Master's singing voice among those of the birds.

'Ah, Cogsworth, there you are.' He gave me a concerned look. 'Have you been there all night?'

'Er, ye......'

'No matter. Come in now; we must ready ourselves.' said Master, munching the remains of his breakfast. I followed him along many dark passages (a simple metaphor of my life) until we entered a tall and resplendent room inside which Master opened a door to a large walk-in cupboard. Rummaging therein he said loudly into it: 'Lots to do. Much to prepare... Understand this, Cogsworth...'

I heard mainly a chewy mouthful of mumbling, but I think he said it will be the most memorable and exhilerating thing I have done to date, and that I will remember it for the rest of my life__with Master, I am never sure how long that might be.

'Thank you, Master.'

'Don't thank me now. If we make it back, then you may thank me. But for now, we must prepare, we must pack, we must train and train hard; understand, Cogsworth? Train, train, train.'

'Yes Master.'

''Now then, I'm going to have to go away for a while. I have some very important business to attend to in a place called Port Ugal. Can I leave you to arrange things this end? It wasn't really a question. 'When I get back, we'll begin the adventure.'

He threw at my feet a large, somewhat battered and frayed, canvas sack with straps attached to it in adjustable loops. 'That should do the trick.' he said, gazing fondly at the thing. 'You''ll find most of what we need in there. So long, Cogsworth. So long.'

And that was that, he left. The door creaked to a close behind him.

Strange, I thought.

Moments later, the door opened again. Master stepped out from the cupboard, dusted off his shoulders, turned, shut the door softly as if trying not to wake it, turned again, and walked in a controlled yet casual manner to the main entrance from where he finally departed.

And still I was left wondering: 'So long.' Master had said. Exactly how long? Master is so complex. What did he mean? By the time I had found a working rule, I had forgotten - if I ever knew - what it was I must measure. And in any case, Master's flying-machine was now abroad with him aboard. But train, he had said, train. Like I said: complex.

Apparently, there are two skies; one called sky and another called Skye. I read about it on thinterweb. They are spelled differently so you can tell them apart. I realise now that the one master intends to visit is the latter, and that is in a land of Scots far away; it is not the one I know. In fact, it is as unknown to me as the working of Master's mind. And I think he lied a bit (surely to ease the effort on my already overburdened brain): there are no trains where we are going. We must walk. I must walk. Master will not carry me. This much we have learned.

And, since he had given no indication of how long, I set about my task lest he return and chastise me for slothiness and such like. Master can be tricksy like that. Unslothy in mind, unslothy in nature a particularly firm matron (firm in manner, that is) used to say to me during one of my stays at the veterinary institution for juvenile and delinquent creatures. Something like that stays with you. Spurred, mainly by fear, I set about cleaning the bag before opening it. The grime of time had soiled its exterior. It reeked of foetid nights and frantic days; it smelled of Master. I opened it with caution.

Peering into its depths was like looking into the shallows of my own mind: it was slopping with inconsequential things. Among the most significant of these were biscuits: innumerable, broken, but still edible; a lengthy coil of something green and moulding; a small hand-written pamphlet entitled: Archery: Master's way (the author, it seems, having written the entire title on his own, presumably with the intention of adding content as and when he had worked out what that might comprise); something sticky in the bottom, reminding me of a lingering ailment I once had; an old penny, found among a weighty collection of dubiously minted coinage...I suppose which may come in handy should we meet a boatman; and a small, framed reminder of hope___I wondered where that had gone.

Clearly, we could not take all of this with us, and I was very keen to keep my burden light, so I stashed most of the items behind Master's chair. The little pamphlet, since it comprised more paper than content, seemed more usefully deployed in the Bowmen of Winston water closet. The penny, however, fitted comfortably in my pocket; it seemed as good a place as any to keep one. 'See a penny pick it up and all that day you'll have a penny,' unless you spend it. But I got to thinking, after wandering around with it thus housed for a day, that it might better be spent with the pamphlet in the aforementioned closet than append my pocket in almost constant agitation of those bodily parts hanging in the vicinity.

The phenomenon of a bag, once emptied of content and thus vacuous, still like looking into my own mind, was impossible to for me to fathom. I put my inconsiderable intellect to more pressing matters. Dare I repair one of those biscuits...? Dare I repair them all?

Master's return came nigh a full week later. He was bronzed and shiny with good health and in his breast raged the lust for adventure. I quaked...like a duck with a bead drawn upon it.

His lustiness, for that is how he preferred to be addressed for a day or two, rearranged everything that I had prepared, and instructed me to load the car while he, deserving of refreshment, set about having it.

'Cogsworth.' he said. 'Are we ready?'

I rearranged his words into a reply. 'We are ready.' I said.

'Then we must go.' And go we went.

Day One: onwards and upwards:

That land of Scots was so, so far away that I had aged a day during the trip. Many times I requested a biscuit. Many times it was denied. We passed water many times. Apparently, the people there call them Locks, but they have no keys for them, Master said.

The brittle glen is actually a soft and a humble place, like a dog's bed at the foot of its master's chair. We rolled along its sinuous path, until finally, we disturbed the dog...and caught a glimpse of its masters, for there was not one, but many. They lay in magnificent repose, towering high above; age old and wise they were and stubborn as clams. Their immense form imbued them with an air of separateness, aloof above all things; with a set of irregularly-shaped noses prodding haughtily at the fluffy bottom of the real sky. To one such as me they spelled foreboding. I could sense their power vibrating in my bladder. Don't tell Master.

Some of the noses of Cuillin

Work to be done. Car to unload. Kit to prepare.

Where was Master?

It seemed that Master was still passing water.

''All set, Cogsworth?'

''Yes Master.'

'Remember Mount Doom?' he asked.

'I do.' I said. And I did. 'I cried like a__'

'Yes, yes. Let's not get ahead of ourselves.' he said. And continuing: 'Mount Doom was but the wiggle of a toe compared to what is to follow.'

Master's face seemed to distort into a frightening shape. I thought it might be a kind of smile, but his eyes seemed a little too wide, and they focussed on a distant place. He chuckled to himself. The packs weighed heavily as I hefted them, judging them to weigh each as much as a bag of taters. The difficulty I experienced with my own burden was that it also included Master's. He explained that in order to be free to explore, not only the physical aspects of the terrain, but also the greater, in his opinion, metaphysical aspects of life, he must not be fettered by such encumbrances, and that it was my place to support him in this endeavour. Of course, he was right. I never doubted it, not even a hundred times. .

I set off at a gallop to catch up because Master walks so fast. Carrying both packs and the climbing gear, including a shiny new heavy rope, spun it seemed from strands of lead, was difficult. I was eager not to crush the repaired biscuits, you see. And since I had no idea where Master had packed them (if he had packed them at all), it was a tricky business trying to keep up. Master says I'm a lagger, a slug-foot, and a tardy turdy bastard. Master is good with words.

'Navigation.' said Master. 'Being able to locate your position, to know where you are at all times, to know your destination and to find it. These are the essential skills required.' he said. I had one answer to each of those categories: just behind Master. I knew where I was. But I hadn't yet learned to worry when Master makes a bold statement. I always presume he is imparting great wisdoms upon me. He has, after all, extensive knowledge beyond the scope of my knowing. I felt sure that somewhere in that vast unfathomable matter between his wax-laden ears was filed a mental repository of maps, routes, and special things to steer us across the noses.

'Now listen here, Cogsterbastard.' Master bad me come close so that he could lean on me and unfold a sheet of paper across my back. He jabbed a finger in it.

'Ooh! That tickles, Master!'

'Be still now, you varicose cheese, I'm trying to take a bearing.' He mumbled for a while. 'Right. We'll go left at that lochan. Then, lookin' right, we should see a hillock there. Straight on, left a bit and then up, up, up, the stair... You get all that, Cogsworth? Cogsworth, wake up, man!'

Master tells me there are many growling mountains up there. Already I can feel the wobbly legs of trepidation destabilizing me. He read aloud some of their names, but I can't remember them all. There is Grrr Alister, Grrr Nanny (I was a bit worried about her), Grrr The Lick...that I can remember, but there are many more. 'Why all so angry?' I asked.

'Master?'

Towards the growling hills he strode. I scurried after him. Master was at the helm, Mapsman, Leader. From the map of Harvey, it seemed that we had about seven miles of path to take, but Master chose only to take about four of them. He is not a greedy man.

'We'll go up Grrr Alister.' declared the Helmsman.

'Isn't that a bit rude, Master? Won't he mind?' I expected and feared the wrath of Alister because he is the biggest nose of all. I felt sure that once he felt the itch of our tiny feet upon his thighs, there would be bother.

Still, Master knows. And freshly inserted in my mind was the additional knowledge that a growling nanny one day may be our target. Dark things ahead. On we marched to find ourselves in a place called Coy Rag Under. I reasonably supposed that if a bare mountain would need anything at all at this altitude, I could see that such a covering might indeed preserve a degree of decency in the likely event that Alister's rocks become exposed. That understanding, however, did nothing to alleve the growing unease I felt about going up his ghrunndapants. Ultimately, to my great relief, we were not where we thought we were, getting only as high as Alister's knees. A place called It's on a Quiche. But at the time, I was convinced we were tramping upon and laying hands upon other areas of the mountain's anatomy. Oh, the things we did. Shame on us.

The long hike into the hills fair drew the puff from me and burned away all but two drops of energy, which finally emancipated themselves as tears a rollin' down my ruddy cheeks.

I can't go on, Master.' I cried. 'I shall die here.'

'Nonsense, man. Get a grip.' said Master in his best tone of concern. 'You'll die when I say you can die.'

'Can I have a biscuit, then?'

If a look from an eye can say no, that is what Master said. His voice, though, commanded more. 'Now then,' he said, firmly, 'in the interests of safety, put his rope around your neck. That way, if you fall, I won't lose you.'

His concern moved me to further tears, but they just came out as dust. Such was the state of my dehydration.

'I am thirsty, Master.' I pleaded.

'Really? I thought you were much older.' he said, coiling rope.

Master had to physically haul me over the boulders and rocks whenever I fell over, which was often. Finally, Master relented. And with a genuinely loving smile, he gave me a drink from his own personal supply. It looked a bit like tea, but without the milk. It was as warm as tea...

Further along the path, and feeling much better now, I listened to Master's ramblings and never fell over once, not for a while, anyway. I began to realise that Master would have quite a bother searching for and finding a substitute if he lost me. (The Register of All Things Subservient is notoriously complete with miscreants and vagabonds, and though every one of them is rated in a much higher status than my own -which is really an absence of status- not one of them knows Master as I do, nor could they hope to.) Master hopped onto a rock and leaped to another...I observed, with affection, the ease with which he moves in the mountains. He is like a mountaineous goat, but with softer feet.

And I know how difficult it has been for Master...

But what's this? Master is still talking while I am thinking. How rude of me.

'.... And, if I'm honest,' he said, 'I don't fancy the messy business of having to scrape you into a bag. It's jolly bad form to leave one's litter on the mountain, you know.' Master said, practically.

Master's edict of the day was that thorough checking and testing of equipment is essential to the success of any expedition. One must be able to rely on each and every one of your bits of kit, he said. I was given the example of my own existence on master's list of useful things. If I had any tears left, I would have been moved to them. My eyelids squeaked against my eyeballs. He explained that I am tested daily, often without my knowing it. Sometimes to breaking point, often to breaking point, so that he may get the best from me (in my head, I thanked him for that), so that he may rely upon my resilience when the time comes. To this end, and to another, I was tied:

'Testing a rope's anchorage is all part of a mountaineer's safety routine.' Master said. Thus, by tying me to a loose end and dropping it over a ledge, Master was able to test many things at once. I need not tell you that all such tests held firm. It is a testament to Master's enduring skill in the mountains. My 'sillyance', it turned out, would be tested beyond even the imagination of a creative person.

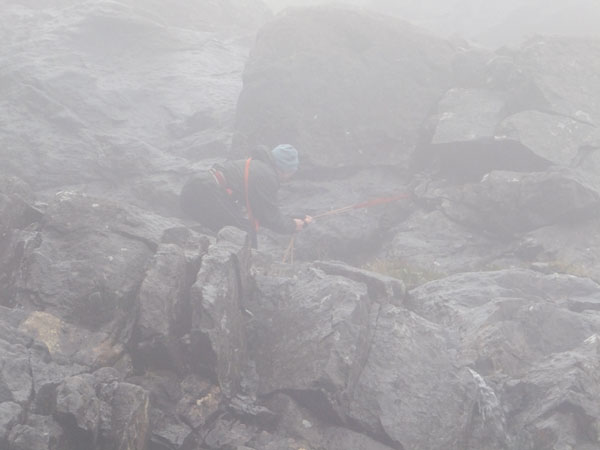

Down there?

Of the the most private of Master's many sounds, the rolling mumble is perhaps the most interesting. Its eerie sound beguiles you with such soft tones as dreams are made of until your little life is rounded with a sleep of reassurance and comfort while at the same time disturbing those very emotions with concerns that Master may well be completely deranged__worrying... in a frayed knot sort of way. Such is the irregularity that is Master. We must endure. And so it was that we came to our first real ascent. Master almost skipped with joy. I almost slipped with something filling my shoes.

After some exploration, flitting from rock to rock, eyeing every crevice, probing every hole, feeling every rounded nub and smoothing slab, Master decreed: 'This way!'

Naturally, I followed.

'Don't slip.' he said. 'It's a long way down!'

My dreary ascent was about as far from Master's flitting as moon is to sun. A mist was descending quickly among the irregular noses, and there was often something slippery running twixt hand and rock which made for precariously slow progress. Master's voice descended through the mist, strangely distant-sounding.

'We must press on, Cogsworth!'

'Pressing, Master!'

'Cogsworth. Can you hear me? Where are you, you turdy bastard?'

'Here Master.' I called.

'Cogsworth?'

At this point, I realised we were having a one-way conversation. Not an unusual activity with Master, but clearly he was trying to hear me, but could not. For an exercise which relies on communication, this did not swell my timid heart with reassurance. 'Here Master!' I yelled.

'Well, speak up man, I can hardly hear you.' came the reply.

'It's a tricky bit, this!'

'This is no time for biscuits, Cogsworth. Get your arse up here now!'

That tricksy bit

'Come out, Cogsworth!'

It seemed like an age had passed before the climb ended. We were both quite tired at this point. Master sent me on ahead to prepare a camp called a bivvy while he attended to a leakage from an area of his anatomy reserved for sitting on. On my return, I marked the site (silent...and invisible, 'h') with a large rock...so that other people might not step in it. After much rustling, and grunting, we settled for the night under an old scrap of roofing material I happened to have been carrying in my pocket since July...2010.

The sky's urination upon us was relentless for the entire night.

Day Two: onwards and downwards:

The morning of day two, began much in the way day one had ended. Mist remained, and rain persisted. But we had tea. Master had tea, I had the drippage of rainwater which I had collected overnight in one of my shoes. When my shoe was empty and the rain had stopped, Master suggested I play in the mist for a while. I didn't want to play.

'Can I have a biscuit, Master?'

At the end of a very long thin sentence, which contained multiple explainatives, Master said 'No.'

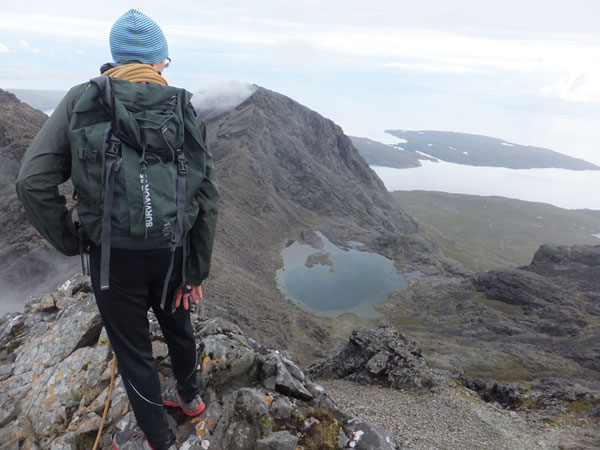

Home

From our bivvy, he sent me out into the mist to find out where on this goddamned planet we were, while he attended a foot wart he had found in his sock. From fear of getting lost, I dragged Master's discarded sock behind me to leave a scent trail so that I might find my way back to him. That was clever of me, I thought. And it worked! But Master was both hopping and mad when I returned an hour later with no definitive information that would assist our escape. He quickly cleared up any issue of doubt I might have had regarding our entry into this predicament, and suggested that since I had managed it, irrevocably, and single-handedly, it would be, once again, up to Master to save the day (his words_more or less).

We packed our things, and marked the bivvy site, which we had called home for a while. this time so that people could find it if they happened to be passing. A discarded shark's fin did the trick. Unsurprisingly, we renamed it Lark's Wing Bivvy. I retraced our steps of the night before by scent (Master's). Communicable diseases, uncontrollable leakage, and persistent rashes can be a nuisance most of the time, says Master, but on this occasion, perhaps the only occasion, they proved to be an asset. A couple of ravens laughed at me on the way, but I didn't mind. I like ravens. And finally, under the steerage of master's dubious helmsmanship we found the edge of the cliff face which was now raging with some rather inconvenient water. I am grateful to him for noticing this latter at the most appropriate time. And I was struck, with some awe (it making a nice change from the more usual stick), how swiftly master was able to then solve the challenge of our descent. Great minds are able to select the simplest solutions in times of need. We, meaning Master, opted for a bastardized version of plumbing a depth at sea. Master was to tie a bit of rope to me and lower me over the edge to learn how far we could descend in the thick mist.

Shouting through the mist, Master said, 'We call it sailing, Cogsworth. Sailing off a cliff.' I did not like the sound of that. Unfortunately for me, one of Master's other peculiarities is that he is endowed with an irregular attention span. On this occasion, it shortness prevented him from remembering that once I had been sent over the edge, it would be necessary for him to keep a controlled, if not firm, hold on the rope. Masters will be Masters.

The impact was not as bad as I had expected. We have so many bones in our bodies that a few broken ones should not give cause for alarm. At least that was how Master explained it to me later. That I could feel pain, he said , meant that I was still alive.

Throwing back the bit of rope to Master proved to be tricky, since it felt as though one of those bones might be in an elbow, and perhaps even, an ankle. But without rope, I would be Masterless at the bottom of a drippy and somewhat austere cliff, so persist I must. And succeed I did. ..'It's just physics.' Master said, when he finally reached me. 'I think we should employ this method more often; it is both simple and quick. In fact, quicker than falling off a cliff, eh? And simpler, even, than you, Cogsworth.' he said, kindly involving me in the science of it. 'Oh. And while you are here,' he added, 'be a good sport and scramble back up. I think I may have left my pack up there.'

In variations of this fashion, we descended three such cliffs and a waterfall. Water is not as soft as it looks.

Dampness coupled with exhaustion can bring about a dangerous condition called hypothermia, Master said. Adding that, since he was neither damp nor exhausted, this would not be a problem. He climbed back onto my shoulders.

'Press on, Cogsworth. Press on.' he said, snapping his fingers by my remaining ear. The damaged one had rotted and fallen off on the journey to this place.

Master told me stories about his conquests and exploits in foreign parts, and we rumbled on for almost a mile of steep descent before Master tugged my ear and yelled: 'Storp!'

'Look there.' he said pointing. But I could not see because of the stoop of my back and Master's foot restricting the the normal swivel of my neck.

'There are deer. Over there, Cogsworth. I must get myself a picture of them. Fetch the painting gear.' he instructed. 'Oils, I think.'

I did as he requested.

Oh, deer.

'Now keep still, Cogsworth. I'll need a steady hand here.'

Master stood on my shoulders for three hours in order to get down the necessary detail, and of course, we were up against it with the light being so changeable up here, he said.

'Nearly done, Cogsworth. You alright down there?'

It must have been my whimpering which drew further attention from him, because he abandoned his painting, an hour later to attend to my knees, which had broken under the strain.

'That's a blessed inconvenience, Cogsworth.' Master said. 'I nearly had the damned thing finished. No matter. get yourself fixed up while I look at things.'

I remembered what Master had told me about perthernia, and panicked a bit. I ran through the mental checklist of things he had said to look for. Shivering? Yes, I was shivering. Exhaustedness? Yes, I was exhaustedness. Unable to speak coherently? 'Sgrr nanny nanny Deargg na Banachdich, sgurrr sgrr..Ghrr.unnda Master's wobblibitz.....'

I panicked again, guzzling biscuits without permission, fortunately Master was busy gazing at heather _ I did not see her, but I imagined that she would be perhaps beskirted and bent to inspect something botanical; encouraging, I suspected, Master's own interest in Bott-any_

I slurped water from the barrel under my chin, and I stripped, wound an entire roll (40m) of baco-foil all around my body, covered myself with a modified bin-liner which made a nice sort of jacket, and to prevent further heat loss, dressed again. I had hoped all the while that Master might assist, for it was difficult keep the foil in place while I pushed my arms through sleeves, but he did not.

'Just look at that heather, Cogsworth.'

When Master returned, he pissed himself laughing.

'Cogsworth. Cogsworth.' he said spluttering between laughs. 'Don't you look the man about town! You steaming great turd. What a lovely picture that would make...if only we had time...and you knees.' he declared, erupting in a tearful fit of mirth and spittle. To Master's credit, he made a considerable effort, then, to put me at ease. Having suppressed his spontaneous eruptions, he said with some honesty that he thought I looked a proper twat. That near lifted my spirits. It is surely a huge step away from being an improper twat, I thought.

But I still wasn't sure what to make of it all. I had nearly died up there! Somewhere in my tender places, I wasn't entirely convinced that Master had meant what he had said. Master's lessons about sarcasm and irony returned to bully my thoughts once again.

Finally, Master's mirth abated, and we were able to continue in the fading light of day. Master fashioned a little song from some spare words and sang it all the way back to the car.

'You all right down there, bastard?' Master enquired with concern absent from his voice.

'Easy as sailing off a cliff.' I re-lied.

'That's the spirit, Cogsworth.' he said.

Day Three: onwards and upwards, and downwards again:

This, the third day, began with the arrival of a rude van driven by the ugliest and most miserablest of near humans I have ever seen. Within the spitting distance of a spitting champion he had parked, obscuring our view of a small hedge we had admired on our arrival. The man strutted to a position between his van and our camp, postured in the manner of an ape, and looked at me for some very long seconds. This activated my hackles, even though, technically, I do not have any, since, as we all know, I have not yet attained the lofty status of dog. Even so, I stood proud and defiant and gave him one of my special stares. For which he said thank you, and offered me one of his fists, which I accepted gratefully in the eye. I went and hid behind Master. The man was a mountaineous guide and I did not like him.

'The pack today must be light.' said Master. 'You can carry my surplus.' Day two repeated then.

Master outlined the plan for me in sufficient detail that I would understand my duties in their entirety.

'We are going up there, today.' he said. An extended arm with a finger on the end of it pointed back to the noses.

Blow the noses! I thought. Blow them all. But of course, I say nothing. Why does everything I do with Master involve going up things...except in the world?

'We mustn't think like that, now must we?' said a corner of my mind reserved for guilt and remorse. I never get a happy lecture from it. Not like Master's; even if you go to sleep, you go to sleep happy.

'Master?' I enquired.

Master turned and frowned quizzically.

'Can I have a biscuit?'

Master's hand described a curving sweep, made contact at its zenith with the side of my head where an ear once lived, and returned to his side from whence it had come.

If he said yes, naturally I did not hear him.

We took a different path__don't we always? Master let slip in his mumblings that we would be again heading for the thighs of Alister. I chose my moment carefully.

'Master?'

'Yes, bastard.'

'Can I__?'

'Nope.'

'But Master__'

'No Biscuit.'

'But I wasn't asking for a biscuit, Master.'

'What then?'

'I wondered where exactly we are going today.'

'Well why didn't you say so. You silly creature. You only had to ask.'

'I did.'

'Well then. There you are. Now please don't bother me while I'm breathing.'

'Yes Master.'

The going got steeper and steeper until it was at such a gradient that one degree steeper would precipitate a shifting looseness of bombastic material which could at the very least graze one's skin and at the very worst shred it and crush it so that one became but a pulpy fiction: a memory. We had arrived at a place called the Great Stone Chute. When stones begin to roll and rocks begin to slide, who are we gonna call? Master had his own ideas about that, he called me. How privileged I am. (sarcastic irony?)

'Cogsworth. You're good with loose things, are you not?'

'Am I?'

'Well yes of course you are. If you are not, you need the practise; if you are, then you are just what we need. Now off you go. Try not to dislodge the entire scree; not to mention those large boulders...and be careful now...I want you to come back for me when you've found a way through.'

'Yes Master. Going now.'

I discovered, just as glaciers must have done, that the gravel and scree make a useful grinding medium should you want to cut great swathes through the solid rock of mountains...or to wear away a creature's legs should he wander in your midst. Three pairs of shoes did I wear way, and as many toes. But I learned that endurance and perseverance bring about success. I think Master was pleased with me. He can be a little picky about his shoes. And I had just saved them from certain destruction. It might have been the extreme altitude, but master actually agreed to think about letting me have a biscuit. Now that's what I call progress! From the top of the Great Stone shooty thing, it was a few short hops for Master, and a thousand trepid shuffles for myself, to climb to the tip of the highest nose. Alister's hooter was shrouded in mist. We danced a jig upon it to celebrate, and descended more swiftly than we went up. Going down is always easier than getting up, you ask any porn star. Which leads me nicely to our next objective: Grr The Lick.

Things were going a little too well. I know about such things. When hardship is the norm, it is natural to be suspicious of ease. Ease is the harbinger of calamity, in my experience. Still, we had little difficulty ascending, in spite of the inauspicious name of the place. Master experimented with ropes again, tying me to his leg while he ran across the cliff-tops; my screams urging him on. But Master is a man of the mountains. A man of flint and grit. For him they hold no fear.Me? I cried like a baby.

'Keep up, Cogsworth.'

He belongs;

He understands their wily ways,

Their fickle nature;

He offered them a sacrifice:

A little frightened creature.

He must have known that all the mountains wanted that day was to hear screams of terror and to witness the pathetic dribblance of a crushed spirit. The Mountains were indeed appeased. While dangling like a participle at the end of an excruciating sentence, that surely being a sentence of death, I pondered the value of my existence and found it to be priceless (that is without price, costing nothing, worth less than something. ). The inestimable sum of my parts amounted to nothing. I had overcome much in the way of hardship and endless deprecation. I had come so far. Once upon a time, I was less than nothing; now I was less than something. That was something, in itself. Something to be proud of. ..

'You still there, Cogsworth?'

'Yes, Master. Can you pull me up now. please?'

He might have warned that I might dangle,

Tipped a nod

Or slipped a wink.

(Seems I've much to learn. )

...surely now,

My Master knows,

A biscuit I have earned.

At least, with the Mountains thus appeased, we could descend without further ado.

Isn't gravity a wonderful thing...generally speaking? What fun we had riding the scree! I called myself Scree Rider. Master called me other things. He allowed me to be the first to reach the bottom. We were never racing, of course. And Master never slipped on his bottom, not five times or more. What fun we had. It had taken over two hours to scramble up; a mere forty minutes to ride it down...maybe a little longer for Master, because we were never racing at all.

The great stone chute... Really great!

Both of us had suffered pain on this trip. I had been, and remained, Master's. Our fingers bled from the abrasion of spiteful rock upon them. The drops of blood accompanied those of sweat and tears we had shed in our endeavours. But the mountains wanted more. They sent out their agents to collect. Tiny buzzing things called, I think, minges, Master said. Bitey buzzy winged things, sent to devour what the mountains had failed to consume. Master was ailed by them; I think they found me a bit gristly and dry, maybes even a tad bitter for their taste. I know, from when I have eaten bits of myself in the past, that I can be a bit chewy. But Master, being juicy and ripe in certain areas, was an easy meal. Locusts in miniature, they came in their thousands to attack. I feared they would eat Master whole. I ran at them to shoo them away, but they dodged aside and rounded on him before I could regroup. Master bent as if smitten. I watched him fold to his knees. And within a second or two, it was all over.

Remember I said that Master was tricksy, well, clever Master simply bent to remove a sock, and wafting it he smote his enemy to the ground, whereupon a great crunching followed as Master stamped upon and vanquished his enemy with a bare verrucad foot until there was but the wafty silence of the moor remaining, and a certain tranquillity of spirit emanating from his ears. He resocked his foot and booted it. And Master said, standing tall,

'C'mon Cogsworth; let's go home.'

My feet trod somehow lighter, and the journey to camp shortened with every step until there were no more to take. We had arrived.

The night folded around us. New challenges lay ahead for those who were prepared to tackle them. New adventures beckoned. We were not prepared, so we packed up camp and moved away to a little spot in the woods two miles away, which in the daylight, we later discovered, was actually a toilet. There were no answers to any of the questions that might have been asked.

But with the blanket of night thrown over the world, we enjoyed a night oblivious to our immediate surroundings, laying supine instead and in wonder at how the blanket came to be pricked with tiny shining holes, coruscant against the darkness.

Master invented a game. The Game of yes or no.

'Starting now, shall we play the game of yes or no?' Master asked.

'Yes, Master.'

'I win.'

We then sat around our camp fire with our suppers, I at Master's feet, listening to his toes while he imparted the teachings for which he is world famous (He told me that). He even treated me to one of his special lectures. Now, it can be dangerous listening to Master's lectures for they are so illuminating the are apt to spontaneously combust. An attentive listener who is tinder dry could get too close and find himself aflame, as I myself have done on many occasions. Among the countless scars Master has gifted me, burns are among the most numerous. But never mind that. It follows, therefore, that Master himself is at risk in the telling.

So imagine my concern when I finally awoke to find myself Masterless with but a heap of ash smouldering before me; I presumed Master must have set fire to himself again. I thought, in a curiously Irish accent, 'this is going to take more than a jar of nard to put right'. How relieved I was when I stood up to see master relieving himself by a tree -- and I must ask him, in a quieter moment, how he can perform that entire function with his hands behind his head. Aah, the idiosyncrasies of Master.

It is a strange experience, spending long periods of time with Master. His numerous afflictions make interesting a time that would otherwise be employed for play, and, I suppose, a pleasing distraction from the tedium of daily chores. Beneath our canopy this night, a gently circulating air, incapable of escape, bore the most insalubrious odours to my nasal cavities where they saturated my mucoidal membranes and lulled me to hypoxic sleep. Meanwhile, the moviture of the earth continues...as do Master's emissions.

Day four: onwards and outwards

Master dreaming

The morning of the last day roused us with benevolent warmth, lifting our spirits and giving us hope once more that horizontal travel remained possible. Time and altitude (and Heather, bless her) had distorted our perception of things. Master said I could play with the camera for a while after I had loaded the car and made his breakfast. That seemed to me to be the wrong order of things, but Master will have his reasons. I managed to contain the fire to the back end of the car until I could put it out with more of Master's delicious tea. But it was soon playtime for me. The sun was shining and I became fascinated by the black pictures that hide behind people and things on sunny days, painting themselves on the ground like that. I put away the camera. It was more fun hurling myself on to the black picture spreading out from my feet to see if I could shape myself and stay within its boundary before it moved. I managed it every time! But Master did not see...and I have not any photographic evidence to back up my claims.

Master had to visit an old man at the other end of the island. Unfortunately, it took us quite a long time to get there. By the time we arrived, the poor gentleman had turned to stone.

'Pity.' was all that Master said.

And then, to make matters worse, on the way back we encountered a Dutch lady and her son who took Master's picture__Thieving bastards. And to think it had taken Master ages to paint not two days ago.

'That was my deer painting.' Master said.

'How much was it worth?' I asked.

Master poked my eye with his finger.

The journey home provided me with opportunities to reflect. The first of these occurred when Master said he smelled gold. We abandoned the car, and ran across the moor to a place where a small waterfall dived into a pool before climbing out to wet some rocks and slither into a tunnel. To get to the gold, Master had to utilize my bridging skills. He lay my stiffened body between two sharp rocks, one of which neatly fitted into my nose. It was a simple task then for Master to walk over me.

'Wait there, Cogsworth. I'll need to use you again.'

We live to serve.

As I waited, I had my first reflection: it was in the water below me.

Master splashed about in the water, running hither and thither all a dither. His pockets were filled with nuggets of gold. He had the fever. Soon, he had his head under the water, peering at the pebbles and sand below.

'Now then, Cogsworth, if I just squint through this peculiar device, I should be able to see...Ah-ha!..'

There comes a time in every bastard's life when he must think for himself. Now I have tried this before, and it has never really worked out for me. Still, Master will drown if I don't get off my rocks to help him; to remind him to breathe. Master was floating, now, face down. The water was carrying him towards the tunnel, bumping his limp body over the rocks, the gold weighing down his lower parts so they grazed and scraped...I reacted with speed and efficiency. Master spluttered back to life in my arms, emptying by means of a highly pressurized squirt, the entire contents of his lungs and parts of his stomach into my unfingered eye.

I rejoiced: 'Master lives!'

'I was never dead you great steaming withering turd!' Master said gratefully. 'I was merely sifting gold from sand with my teeth. Look here.'

He pointed.

Master had indeed a golden tongue...and gumfulls of sand. His face had rounded into a shape unmasterlike. But in his eye remained a glint. Had some of the gold become lodged there? Certainly there was gold in his eye, metaphorographically. I realised, suddenly, that I was witnessing a hitherto unwitnessed event. Master was acquiring yet another affliction. It was a very special moment. Another facet had been added to Master, bringing the total, now, to two. Veritably, a multifaceted individual he is. Pride swelled in my breast and made me burp.

With the car now laden, we made slow progress. Master asked if I'd like to play his game of yes and no. Of course, I said yes. He won that round.

'Shall we play it again?' he asked.

'Yes, Master.'

'I win!'

We played the game six more times. I have to admit, I was becoming weary of it. So when Master asked once again, I felt obliged to say no. And no I said.

'I win.' said Master.

Mountains began to round into hills, and hills seemed to remain hills for quite some time before softening to teh undulating countryside of familiar land. We were nearing home.

'One day,' said Master, 'we shall return to those mountains and conk-er all the other noses.' He went on to say that some people like running noses; Master says he prefers to climb them.

We nestled into that warm bosom that is the last few miles home. Few words were spoken. The issue of a sigh, or a broad smile, conveyed the sentiment of events re-lived. Master scratched himself and sniffed his finger.

'Not long now, Cogsworth.' he said.

Ever the soft thrub of the engine's voice lulled us further to relax as we wended our way down our little setting-off lane. As we rounded the last corner, the end wall of the palace came into our headlights. Master had forgotten to brake.

I have made an epic-log:

Master came rushing into the pantry of his great palace. ( It has suddenly occurred to me that a palace is just a place. How odd. )

'Bastard.' he called. 'Bastard. Where are you? Ah. there you are. Need I ask why you are lying upside down under that table? Put some clothes on, man. You'll catch your death. No matter. Listen, you steaming great turd, I have just had the most excellent of ideas...'

Master put on a glove, and dragged me from under the table. My skin gave a little squeaking sound on the cold stone floor like the nose of a dog I once knew who would habitually try to hide bits of his food under the furniture in his kennel by pushing it there with his nose; it (his nose, that is, less often his food) used to squeak when it rubbed against the polished marquetry of the wooden floor. Master tucked a small roll of paper between my toes before going on to tell me what his idea was. He then left, tossing the glove into one of the many palatial fires burning in their hearths.

It would be up to me to sort out the details, he had said. The hardest of the work had already been done by him in the thinking of it, he had said, his words returning to me as I unfurled the paper scroll. It looked like a set of plans. I was to design from Master's briefs, some sort of site which I supposed would be for spiders to play in. This I was to attach to a named domain which I was then to launch over the workings of some kind of net that was not made from anything you could touch and which would not catch anything useful... My little brain fried and burst. But there was more... The few bits of my brain that were still working, I gathered onto the head of a pin and poked back inside my skull, and read on. We were to have a clubhouse, Master and me. And he would have a chair within it..and everything. Master has excelled even the finest of his own achievements, I thought. Master is a genioid.

I built the whole thing under the sink before Master returned for a pie later on.

'It'll have to be bigger, bastard.' he said, surveying my work with his pocket theodolite. 'But I like what you've done with the place.' Now then, did he mean place...or palace? I dare not ask.

Master further hinted that instead of biscuit, there may be cake! What joy!

'Bash on, Cogsworth.' he said. 'Bash on.'

With theodolite deep in pocket and still firmly in his grasp, Master walked away with a little wiggle to his hips; his special blanket swishing behind him like a cape in a wind of his own making.

And so was born the home of The Winston Archers of the Tees. We move in today.

This is a slightly less epic-log:

My ear has begun to grow back, and so have two of my toes.

And we have decided that instead of just bringing back painful memories, we should also bring back some part of the place that caused them.

Totally unrelated to this decision is the news that I unintentionally brought back several shards of stone from the Great Shoot in one of my shoes: the one that I drink from. We now have a considerable pile of stones and other matter behind Master's chair....stones, and relics collected from our other expeditions into the unknown. The clubhouse is now a-burgeoning. We have settled into it very well. Master has a new toy called a Kindle Surprise which enables him to see all over the world. I worry that he is spending too much time on the thing. One can have too much of a good thing, I reminded him. He reminded me of my absence of status and drew my attention to the amount of biscuits I had consumed lately. I dare not challenge the statistical inaccuracy of the latter, but he was, of course, quite correct in the former.

'We need to be fitter, stronger...wealthier.' said Master, suddenly springing from his chair to snatch a wedge of cake from a plate. 'You must train...and earn.' he said, chomping. 'Earning is just Learning without the 'ell.' of it.' said Master informatively. A piece of the cake's filling squidged onto Master's chin as he bit into it. Instinctively, he brought a dextrous digit up to his face and redirected said squidge towards his mouth. 'You thought Skye was the limit, Cogsworth, wait until you learn of our next adventure!'

My bowel slackens at the thought.

____________________________________

So, which one is the Old Man?